In the fall of 2012, I seized the opportunity to do some research I’ve wanted to do for a long time. Millions of users would be available and motivated to take part. But I needed to figure out how to do a very large study in a short time. By large, I’m talking about reviewing hundreds of websites. How could we make that happen within a couple of months?

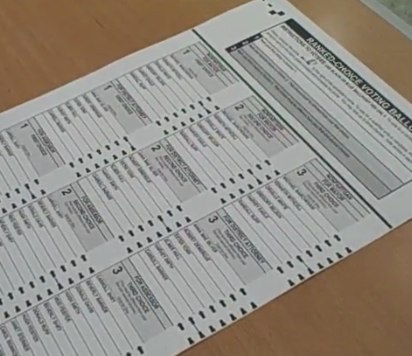

Do election officials and voters talk about elections the same way?

I had BIG questions. What were local governments offering on their websites, and how did they talk about it? And, what questions did voters have? Finally, if voters went to local government websites, were they able to find out what they needed to know?

Brain trust

To get this going, I enlisted a couple of colleagues and advisors. Cyd Harrell is a genius when it comes to research method (among other things). Ethan Newby sees the world in probabilities and confidence intervals. Jared Spool came up with the cleverest twist, which actually prevented us from evaluating using techniques we were prone to use just out of habit. Great team, but I knew we weren’t enough to do everything that needed doing.

Two-phases of research: What first, then whether

We settled on splitting the research into 2 steps. First, we’d go look at a bunch of county election websites to see what was on them. We decided to do this by simply cataloging the words in links, headings, and graphics on a big pile of election sites. Next, we’d do some remote, moderated usability test sessions asking voters what questions they had and then observe as they looked for satisfactory answers on their local county websites.

Cataloging the sites would tell us what counties thought was important enough to put on the home pages of their election websites. It also would reveal the words used in the information architecture. Would the labels match voters’ mental models?

Conducting the usability test would tell us what voters cared about, giving us a simple mental model. Having voters try to find answers on websites close to them would tell us whether there was a gap between how election officials talk about elections and how voters think about elections. If there was a gap, we could get a rough measure of how wide the gap might be.

When we had the catalog and the usability test data, we could look at what was on the sites and where it appeared against how easily and successfully voters found answers. (At some point, I’ll write about the usability test because there were fun challenges in that phase, too. Here I want to focus on the cataloging.)

Scoping the sample

Though most of us only think of elections when it’s time to vote for president every four years, there are actually elections going on all the time. Right now, at this very moment, there’s an election going on somewhere in the US. And, contrary to what you might think, most elections are run at the county or town level. There are a lot of counties, boroughs, and parishes in the US. And then there’s Wisconsin and New England where elections are almost exclusively run by towns. There are about 3,057 counties or equivalent. If you count all the towns and other jurisdictions that put on elections in the US and it’s territories and protectorates, there are over 8,000 voting jurisdictions. Most of them have websites.

We decided to focus on counties or equivalents, which brings us back to roughly 3,000 to choose from. The question then was how to narrow the sample to be big enough to give us reliable statistics, but small enough to gather the data within a reasonable time.

So, our UX stats guy, Ethan, gave us some guidance. 200 counties seemed like a reasonable number to start with. Cyd created selection criteria based on US Census data. In the first pass, we selected counties based on population size (highest and lowest), population density (highest and lowest), and diversity (majority white or majority non-white). We also looked across geographic regions. When we reviewed which counties showed up under what criteria, we saw that there were several duplicates. For example, Maricopa County, Arizona is highly populated, densely populated, and mostly racial minorities. When we removed the duplicates, we had 175 counties left.

The next step was to determine whether they all had websites. Here we had one of our first insights: Counties with populations somewhere between 7,000 and 10,000 are less likely to have websites about elections than counties that are larger. We eliminated counties that either didn’t have websites or had a one-pager with the clerk’s name and phone number. This brought our sample down to 147 websites to catalog. Insanely, 147 seemed so much more reasonable than 200.

One more constraint we faced was timing. Election websites change all the time, because, well, there are elections going on all the time. Because we wanted to do this before the 2012 Presidential election in November, we had to start cataloging sites in about August. But with just a few people on the team, how would we ever manage that and conduct usability test sessions?

Crowd-sourced research FTW

With 147 websites to catalog, if we could get helpers to do 5 websites each, we’d need about 30 co-researchers. Could we find people to give us a couple of hours in exchange for nothing but our undying gratitude?

I came to learn to appreciate social networks in a whole new way. I’ve always been a big believer in networking, even before the Web gave us all these new tools. The scary part was asking friends and strangers for this kind of favor.

Fortunately, I had 320 new friends from a Kickstarter campaign I had conducted earlier in the year to raise funds to publish a series of little books called Field Guides To Ensuring Voter Intent. Even though people had already backed the project financially, many of them told me that they wanted to do more, to be directly involved. Twitter and Facebook seemed like options for sources of co-researchers, too. I asked, and they came. All together, 17 people cataloged websites.

Now we had a new problem: We didn’t know the skills of our co-researchers, and we didn’t want to turn anyone away. That would just be ungrateful.

A good data collector, some pilot testing, and a little briefing

Being design researchers, we all wanted to evaluate the websites as we were reviewing and cataloging them. But how do you deal with all those subjective judgements? What heuristics could we apply? We didn’t have the data to base heuristics on. And though Cyd, Ethan, Jared, and I have been working on website usability since the dawn of time, these election websites are particular and not like e-commerce sites and not exactly like information-rich sites. Heuristic evaluation was out of the question. As Jared suggested — and here’s the twist — let the data speak for itself rather than evaluating the information architecture or the design. After we got over the idea of evaluating, the question was how to proceed. Without judgement, what did we have?

Simple data collection. It seemed clear that the way to do the cataloging was to put the words into a spreadsheet. The format of the spreadsheet would be important. Cyd set up a basic template that looks amazingly like a website layout. It had different regions that reflected different areas of a website: banner, left column, center area, right column, footer. She added color coding and instructions and examples.

I wrote up a separate sheet with step-by-step instructions and file naming conventions. It also listed the simple set of codes to mark the words collected. And then we tested the hell out of it. Cyd’s mom was one of our first co-researchers. She had excellent questions about what to do with what. We incorporated her feedback in the spreadsheet and the instructions, and tried the process and instruments out with a few other people. After 5 or 6 pilots, when we thought we’d smoothed out the kinks, we invited our co-researchers to briefing sessions through GoToMeeting, and gave assignments.

To our delight, the data that came back was really clean and consistent. And there were more than 8,000 data items to analyze.

Lessons learned: focus, prepare, pilot, trust

It’s so easy in user research to just say, Hey, we’ll put it in front of people and ask a couple of questions, and we’ll be good. I’ve been a loud voice for a long time crying, Just do it! Just put your design in front of users and watch. This is good for some kinds of exploratory, formative research where you’re early in a design.

But there’s a place, too, for specific, tightly bounded, narrowed scope, and a thoroughly designed research study. We wanted to answer specific questions at scale. This takes a different kind of preparation from a formative study. Getting the data collection right was key to the success of the project.

To get the data collecting right, we had to take out as much judgement as possible for 2 reasons:

• we wanted the data to be consistently gathered

• we had people whose skills we didn’t know collecting the data

Though the findings from the study are fascinating (at least to me), what makes me proud of this project was how we invited other people in. It was not easy letting go. But I just couldn’t do it all. I couldn’t even have got it done with the help of Cyd and Ethan. Setting up training helped. Setting up office hours helped. Giving specific direction helped. And now 17 people own parts of this project, which means 17 people can tell at least a little part of the story of these websites. That’s what I want out of user research. I can’t wait to do something like this with a client team full of product managers, marketers, and developers.

If you’d like to see some stats on the 8,000+ data items we collected, check out the slide deck that Ethan Newby created that lays out when, where, and how often key words that might help voters answer their questions appeared on 147 county election websites in November 2012.

Hi Dana,

This, like all the other posts, is pure gold! Thank you for sharing it.

As a user researcher team of one, I’ve always longed for the opportunity of a formidable team to work on projects with (not exactly but the type that you have:). What advice can you give me on how to go about this?

Thank you for all the generosity,

Lots of regards

Shakir